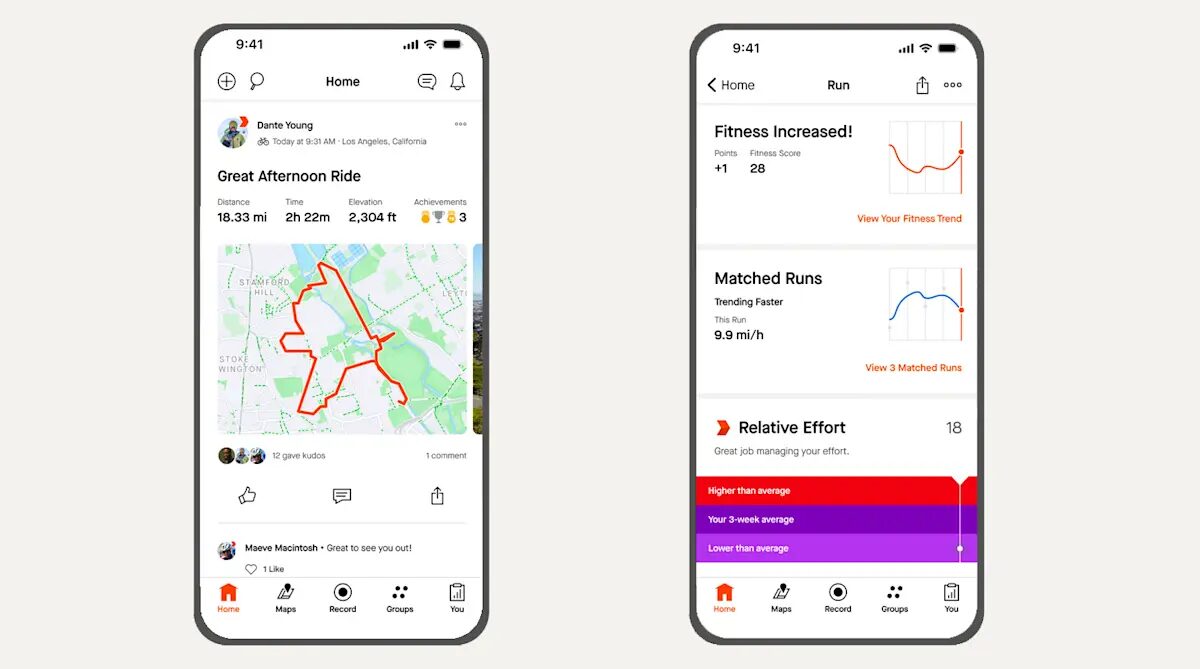

“I’d be gutted if Garmin data stopped syncing with Strava,” said Sue Kay, a professional triathlete and a fitness coach. “Garmin gives me the data, but Strava gives me the people.”

That fear, shared by millions of athletes, fueled weeks of speculation over whether Garmin’s devices would stop syncing with Strava’s platform on November 1, 2025. The concern arose after Garmin updated its API policy, requiring third-party platforms to display visible attribution, a condition Strava initially resisted, citing design integrity and user experience concerns.

However, as of mid-October 2025, Strava has confirmed that it will comply with Garmin’s new API branding requirements, ensuring uninterrupted data flow between the two platforms. This means activities recorded on Garmin devices will continue to upload automatically to Strava, now accompanied by visible “Garmin-sourced data” attribution.

Yet, the resolution of this API dispute does not close the legal chapter between the two companies. The patent infringement lawsuit filed by Strava against Garmin, covering its core technologies for heatmaps, routing, and segments, still stands.

This analysis unpacks the evolution of the Strava–Garmin partnership, the key events that led to the lawsuit, and the patents at the center of the conflict. It also explores how similar technologies exist across other industries, and what the dispute could mean for athletes, developers, and the connected fitness market.

The Evolution of a “Perfect” Partnership

Garmin’s early leadership in GPS-enabled wearables positioned it as the primary data collection point in the endurance sports market. Its devices became the foundation for precise, multi-sensor data acquisition.

Strava, founded in 2009, added the analytical and social layers missing from Garmin’s ecosystem. Its segment-based competition model and performance analytics turned static activity logs into dynamic comparisons.

As both companies grew, their integration created a mutually beneficial loop: Garmin’s devices generated structured data, and Strava’s platform visualized and contextualized it.

In 2015, the companies formalized this relationship through a Master Cooperation Agreement (MCA). The MCA permitted Garmin to integrate Strava Live Segments into its devices, allowing users to view real-time performance metrics directly from Strava’s servers. The agreement included clear restrictions designed to protect Strava’s proprietary algorithms and user experience models.

For several years, the collaboration functioned effectively. However, as Garmin expanded its own software and data analytics capabilities, the distinction between integration and competition began to narrow.

Cooperation to Competition

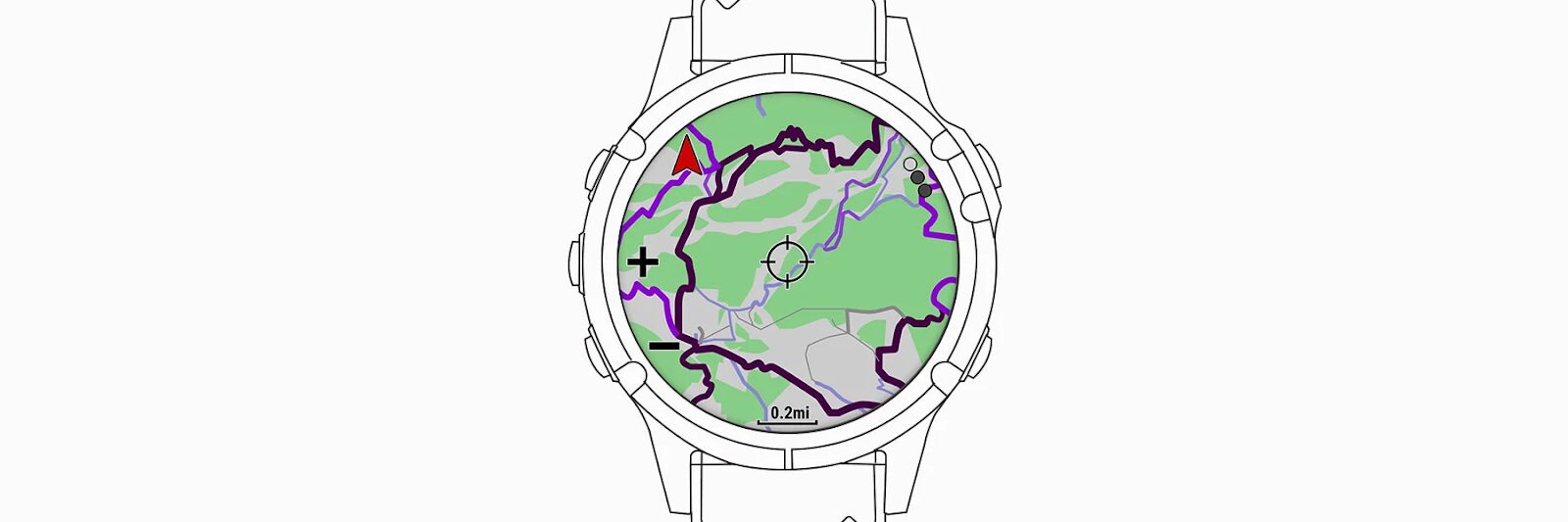

Between 2016 and 2023, Garmin enhanced its platform, introducing new software capabilities that began to overlap with Strava’s patent portfolio. Among them were Garmin Segments, Trendline Popularity Routing, and Garmin Heatmaps.

These functions offered on-device segment tracking and route recommendations derived from aggregated user activity data.

Strava viewed these developments as an encroachment on its patented features and proprietary algorithms. The company alleges that Garmin used its exposure to Strava’s segment technology under the 2015 MCA to design similar functions within Garmin’s ecosystem, exceeding the scope of licensed use.

Garmin has taken the position that these tools were developed independently, utilizing its own dataset and engineering capabilities, and that any similarities reflect standard practices in route mapping and performance comparison technologies.

The dispute over intellectual property remained contained until a new conflict emerged around data access and attribution in 2025.

The API Ultimatum and the Spark That Lit the Fuse

In mid-2025, Garmin introduced an update to its API access guidelines, which set new conditions for third-party platforms using Garmin data. One of the most notable requirements was the mandatory display of Garmin branding on all data visualizations or activity summaries derived from Garmin devices.

Garmin justified the change as a means of maintaining brand visibility and transparency in data sourcing. Strava objected, arguing that the new rule effectively imposed unwanted branding within its application interface and disrupted the neutrality of its user experience.

Initially, Strava refused to implement the change. Garmin, in response, threatened to suspend Strava’s API access by November 1, 2025, which would have disabled the automatic upload of data from Garmin devices to Strava’s servers. This feature is central to the daily experience of millions of athletes.

In a notable turn of events, Strava has since agreed to Garmin’s API branding terms to prevent disruption to its user community. “Uninterrupted connectivity for the segment of our community that uses Garmin remains our top priority,” stated the company.

The Patents at the Heart of the Battle

Strava’s legal claims rest on three U.S. patents that form the foundation of its platform technology:

The Segment Patent (US 9,116,922)

The patent defines a method for creating user-generated virtual race sections on maps, enabling the comparison of all future activities recorded along those paths. Users can define a segment, upload their data, and have it automatically matched to existing routes to generate leaderboards and comparative statistics.

While this innovation revolutionized competitive tracking among athletes, similar logic applies across other sectors:

- Traffic Analytics: Systems like the UK’s SPECS average-speed cameras monitor vehicles between defined start and end points, mirroring Strava’s virtual “start” and “finish” lines.

- Gamified Mapping: Early location-based games such as Parallel Kingdom and Geocaching used virtual checkpoints to compare or trigger user activity in physical spaces.

- GIS and Transportation Research: Map-matching algorithms, including those based on Fréchet Distance and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), have long been used to align real-world trajectories with known routes, a core function of Strava’s matching system.

From fleet optimization to pedestrian mobility studies, the ability to recognize, compare, and analyze repeated movements over consistent paths remains essential.

The Heatmap Patent (US 9,778,053)

The patent outlines a process for collecting, filtering, and aggregating GPS-tracked activities into visual maps that highlight popular routes. This is what Strava calls “user preference activity maps.” The data-driven visualization reveals which roads, trails, or paths are most frequently traveled.

Outside of sports, similar aggregation models have become critical in data visualization and navigation:

- Navigation Systems: Both Google Maps and Waze had integrated heatmap-style traffic visualizations to depict congestion and route density before 2015.

- Social and Location Services: Platforms like Panoramio and Foursquare Explore created visual or ranked “hotspots” of user activity, transforming engagement data into popularity maps for tourism or business discovery.

- Urban Planning: Research from MIT’s Senseable City Lab and similar institutions used anonymized GPS data to identify mobility patterns in cities, demonstrating how such heatmaps could inform infrastructure, safety, and sustainability planning.

Today, heatmap-style aggregation models are applied across logistics, mobility analytics, retail strategy, and even public safety. Basically, wherever collective behavior helps optimize routes or operations, it is beneficial.

The Routing Patent (US 9,297,651)

Strava’s Routing patent builds upon its heatmap system, using aggregated activity data to generate personalized route recommendations between two points. Instead of simply finding the shortest path, it factors in user preference, elevation, and popularity, reflecting real-world trends in human mobility.

This methodology has significant overlap with other domains that rely on crowdsourced or data-informed routing:

- Traffic Navigation: Waze and Google Maps apply the same principle, aggregating millions of GPS traces to recommend optimal paths based on real-time and historical travel data.

- Social Mapping: Services such as Foursquare and Panoramio infer preferred destinations by aggregating user check-ins or uploads, similar to Strava’s use of activity frequency.

- Urban Mobility Analysis: In transport and planning research, trajectory data have long been used to derive “desire lines”. Right from routes most frequently taken by people, informing path design, pedestrian safety, and micromobility infrastructure.

The ability to infer preferences from aggregated data is now integral to systems in logistics, smart cities, and environmental monitoring, showing how Strava’s routing logic extends well beyond fitness.

Implications for Athletes and the Market

In a conversation with Sue Kay, an endurance runner who has used both platforms for years, she summarized the user sentiment clearly: “Garmin gives me the data, but Strava gives me the people.” Her observation highlights the tension that sits at the center of this dispute, the intersection of data control and community reach. For athletes, Strava is more than an analytics dashboard; it is the ecosystem where performance becomes connection, and individual efforts turn into shared experiences.

With Strava’s decision to comply with Garmin’s updated API terms, the immediate uncertainty that loomed over the fitness technology community has eased. The feared November 1 cutoff, which could have severed automatic synchronization between Garmin devices and Strava, will not take place. Data flow continues as before, though with one visible change: Garmin’s attribution now appears wherever Garmin-sourced data is displayed.

Garmin’s devices remain indispensable for accuracy and reliability, but its closed community model limits user visibility. Strava’s open network, in contrast, links users across brands, Garmin, Suunto, Coros, Apple, offering a unified space for social validation and comparative performance. That interconnectivity is precisely what Garmin’s API leverage had threatened to disrupt, and what Strava’s compliance has now preserved.

However, maintaining access does not mean the conflict is resolved. The patent infringement lawsuit still stands, and its outcome will likely influence how future partnerships between hardware and software companies define ownership of the data pipeline itself. What began as a dispute over branding has evolved into a test case for how intellectual property, data rights, and interoperability co-exist in the connected fitness economy.

The current equilibrium, where data flows but litigation continues, mirrors broader industry trends. Similar patterns appeared earlier in 2025, when Google deprecated its Fit API and required developers to migrate to Health Connect. That transition forced app developers to rebuild integrations, reauthorize access, and temporarily lose features until compliance was achieved. Although that case was technical rather than legal, it revealed the same structural fragility: ecosystems built on shared APIs are only as stable as the agreements that govern them.

From GreyB’s perspective, the Strava–Garmin episode marks the early stage of what can be described as the API Accountability Era. In this new phase of platform collaboration, every relationship between device manufacturers and software platforms must address three non-negotiables:

- Attribution rights: who gets visible credit when data is displayed.

- Data sovereignty: who owns, governs, and monetizes the flow of user data.

- Continuity guarantees: how long API access is protected, even when partnerships strain or dissolve.

These principles extend well beyond fitness. The same questions are emerging in EV telematics, digital health ecosystems, and IoT analytics, where APIs serve as the backbone of interoperability and commercial value. The Strava–Garmin case could therefore become a defining precedent, a model for how future partnerships balance competitive independence with cooperative data sharing, ensuring innovation continues without compromising ownership or trust.

Conclusion

With the API dispute resolved, attention now turns squarely to the courtroom. At its core, this case asks a deceptively simple question:

Who owns your workout data?

The eventual outcome could reshape the rules of collaboration across the fitness technology landscape. A ruling in Strava’s favor could strengthen the ability of software platforms to assert control over analytics and visualization technologies, even when they depend on third-party data. A decision favoring Garmin might reaffirm the independence of hardware makers to develop parallel tools without risking legal exposure.

As the case progresses, the industry watches closely, not out of curiosity, but necessity. The result will determine how future partnerships balance innovation with interoperability, setting a precedent for every company building its ecosystem around shared data and connected experiences.