We recently closed a prior art search where our client, from one of the leading infant food formulation companies, was in a tough spot as their competitor had sued them for one of their inventions. Unfortunately, only a couple of days were left for the hearing of this case, and he approached us with little hope.

As we strained through our search options, we feared we may have reached a dead end. However, only when we connected some information from non-patent literature with hidden details in patent references could we give the client some breathing room.

Sounds thrilling, right? It felt that way too. Continue reading, and you’ll see!!

But before we jump on the rollercoaster of our search, let’s start with some background information.

Background of Subject Patent – US’XYZ

The idea behind the patented concept is to reduce the likelihood of developing allergies to common food allergens by including them in baby formulas in lower concentrations so babies can develop tolerance to these products early. The patent requires at least three of the 20 allergens to be present in the formulas, with each allergen having an equal amount of protein content. This means that the protein content of each allergen must be the same, regardless of the weight of the allergen.

For instance, if we have three allergens having a particular quantity (say 10g) having the following protein contents (hypothetical) –

- 10 g of an egg having 2 g of protein

- 10 g of wheat having 1 g of protein

- 10 g of fish having 0.5 g of protein

Although the quantity of allergens (10g) is equal here, still this reference is worthless as the associated protein values (2g, 1g, 0.5g) are different, and we needed to locate these equal values of protein content for each allergen irrespective of the allergen weight itself.

And now you’re all caught up. So, it’s time for the roller coaster!

Challenges During the Initial Stages

We became aware of the case’s criticality as soon as we understood the project. This was due to the following factors:

First, the prosecution history revealed several references, but all the pertinent ones we believed may be used were already discussed. What terrible luck !!

Additionally, in the prosecution history examiner cited a reference from a cookbook that listed all the ingredients but did not specify the amount of protein, so from this, we realized that this information would be scarce in the patent domain and we’ll need to go one step further to find the client the best solution.

This was just the start of it. The roller coaster had a lot in store for us.

Ups, Downs, and the Unexpected Twists

We sure did find results, A LOT, actually. However, we encountered numerous huddles during our analysis. I am gonna list down a few to give you a clearer picture.

1st Hurdle– the subject reference contained a list of about 20 allergens we needed to check for, making it rich in numerous claim elements.

2nd Hurdle- Running search strings/queries with all the potential permutations for each allergen was massive work because we needed at least three of the 20 allergens in the group.

3rd Hurdle– While executing the search strings/queries, the number of references appeared to be huge. This suggested that this domain was crowded, and we needed to prepare ourselves to evaluate as many references as possible.

4th Hurdle– Protein is an inherent property of every ingredient. So, this information was not explicitly mentioned in the references, and only a quantity of allergens was mentioned.

Not only this, we investigated products on Instagram, Amazon, LinkedIn, and other sites to make sure we left no stone unturned. Additionally, we physically went to shops to check if any items disclosed these allergens and the requisite protein content on the product packaging. Still, they merely indicated the ingredient’s presence and showed no indication of the protein content.

Navigating the Highs and Lows

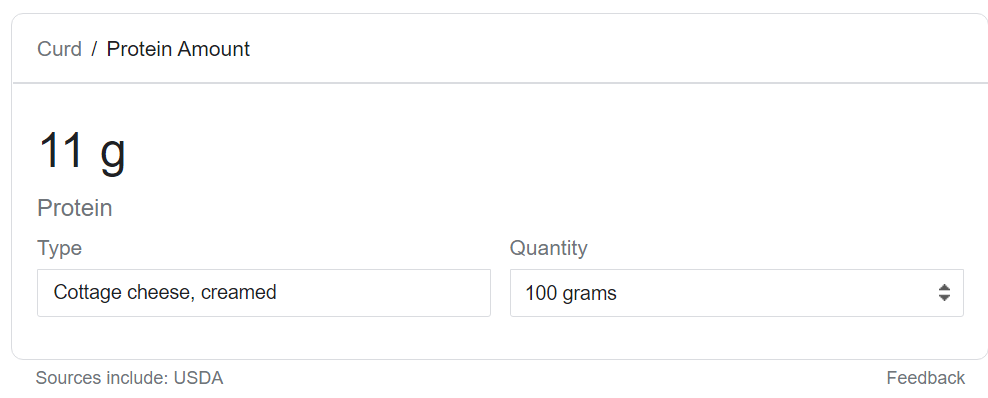

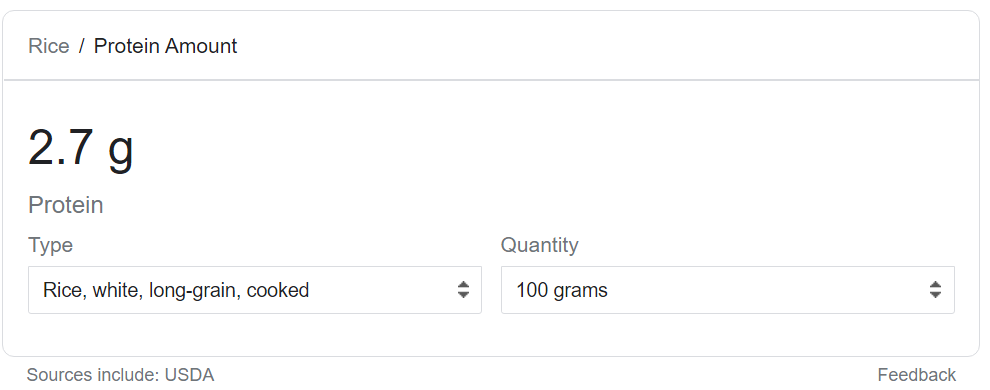

After having back-to-back failures, we kept looking for suitable prior art, and finally, we discovered it on the USDA web page. The trusted regulatory body mentioned that each ingredient or allergen has some hereditary protein quantity in itself, for instance:

Protein in 100 g of curd – 11 g

Protein in 100 g of rice – 2.7 g

We verified this data using a simple Google search. We searched the amount of protein in various food products. The snippets are provided below-

By connecting these dots, we realized it would be ideal if we could calculate the proteins based on the number of allergens listed in the patent literature.

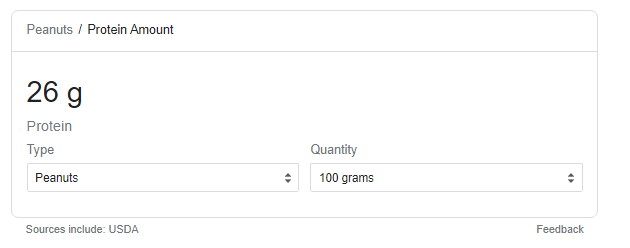

What Next? We quickly Googled the protein content for each allergen. Then we began computing protein values by keeping 100g as the reference to ease the calculations by the weight values of each allergen provided in the patent references.

Here’s how we determined the protein values from the relevant weights:

1. First, we looked up the protein amount for each allergen in 100g from reliable sources like USDA. For example, here is a snippet of the amount of protein 100 g of peanuts has.

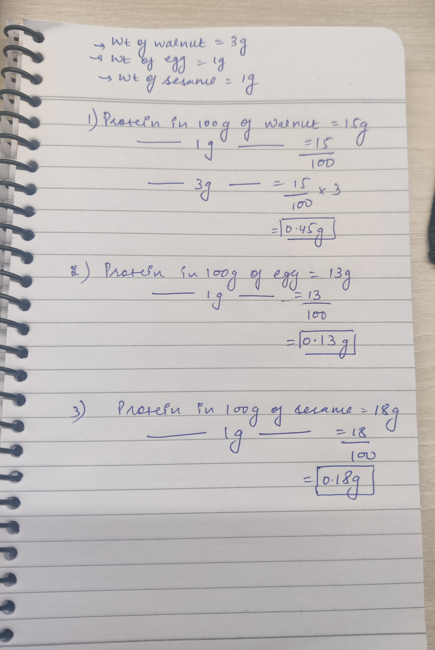

2. Next, after analyzing ~1000+ references (which either did not disclose protein values or weight of allergens or our required allergens), we used permutations and combinations to make all the possible combinations to inculcate our required allergens. We then finally landed onto one reference CNXXXXXXXA which had at least 3 of our required allergens and which was also disclosing the weight [check the below snippet disclosing weights of walnut (3g), eggs (1g), and sesame (1g) ] then we began to calculate the weights of each of the necessary allergens included in this reference –

- The results were as follows:

Our Aha moment

As you can see, the protein content of allergens is almost equal (0.45, 0.13, and 0.18 g). Looking at this, we immediately shipped it to the client and gave a detailed walk-through over a call, given the urgency at his end.

We noticed that the client took the printout of our reference and was constantly looking at the calculations part by comparing it with the values we provided from the USDA data (it showed that they were in a tough spot and in great need of a good reference). Finally, after sharing our analysis in detail, our client was convinced and appreciated our efforts. They had no such reference in hand, which was disclosing all the protein values in equal amounts, especially before the cut-off date. Elated, he said, “this seems to be really helpful and could be argued at the hearing”.

An end to the Wild Ride of Challenges, Successes, and Lessons Learned

Learnings are iterative, and every case teaches us something new. For example, this case taught us how to use information from one source and connect those dots with other information to get insight and provide a potential solution. Suppose we ever receive similar requests in the future requiring us to calculate the inherent properties of ingredients such as protein, fat, vitamin, and mineral content. In that case, we can calculate these values by combining the information in the prior art with calculative information in the non-patent literature.

A patent reference may initially seem irrelevant when it doesn’t provide all the details we need. But, if we try to combine it with information from other reliable sources, we find that the patent contains some hidden facts that could elevate it to the status of 102 prior art references.

The same thing happened when one of my colleagues was working on a GU-related patent; she found prior art in a Jurassic Park movie.

Authored By – Nandini and Divyani, Life Sciences.